Laminitis is a major health concern, especially in horses and ponies who are overweight. It’s one of the most serious and debilitating conditions affecting the equine population, which can quickly lead to a big veterinary bill or claim on your horse health insurance.

As grass grows in summer and autumn, vets see more cases of horses and ponies with laminitis.

Spring is also a worry as this is when grass starts to grow and, when eaten by equines who haven’t lost weight over the winter, horses pile on more weight and become high risk of suffering laminitis.

What is laminitis?

Laminitis is a common and extremely painful condition involving the feet of horses and ponies, and it can lead to euthanasia in particularly bad cases.

Laminitis is an inflammatory condition that causes pain, so many of the symptoms associated with it are signs of pain or inflammation.

Symptoms range from mild hoof cracks with no lameness to severe signs such as not being able to stand or walk.

It can cause the hoof wall to grow abnormally, so other signs include irregularities in the hoof. Note that a mild bout of laminitis can quickly progress to a severe case.

Early signs

Early signs of laminitis can be hard to spot, as equines can show different symptoms, depending on the severity of the condition.

In fact, research conducted in 2018 showed that many owners struggle to recognise some of the signs of a horse with laminitis.

The study found that 45% of owners were unable to recognise their horses were suffering from the disease, resulting in the animals going undiagnosed and untreated.

Laminitic vs healthy hoof

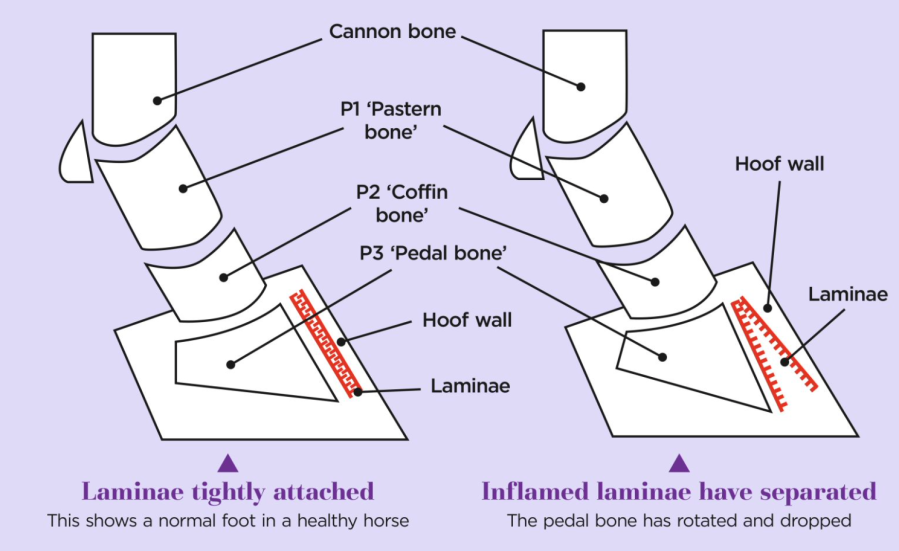

To begin to understand laminitis we first need to understand what is normal for a horse’s foot.

The diagram below illustrates a healthy hoof compared to a laminitic hoof. Note the changes to the laminae and pedal bone position:

Healthy hoof

In a healthy horse, the pedal bone is suspended within the hoof capsule. The hoof wall and pedal bone are joined together by finger-like projections that form tight bonds, called laminae.

One set of laminae is attached to the hoof wall and the other is attached to the pedal bone. These two sets of laminae are tightly bonded like Velcro. This allows the horse to evenly distribute their weight throughout the foot.

Laminitic hoof

When a horse develops laminitis, the laminae become inflamed and begin to separate, which weakens the tight bond between the hoof wall and the pedal bone.

When the horse bears weight on a laminitic hoof, the pedal bone can rotate downwards. This is an extremely painful process and helps to explain why, when a horse has laminitis, a vet may recommend box rest.

This is not just to restrict grazing, but to restrict movement to further prevent the separation of the laminae and avoid rotation of the pedal bone.

In severe cases of laminitis in horses or ponies, the pedal bone can rotate and pierce the sole of the foot, leaving euthanasia as the only option.

Three triggers of laminitis

Our understanding of the causes of laminitis in horses has improved dramatically in recent years.

Historically, it was always thought that access to lush grass was the main cause, but we now know this not to be true.

Laminitis in horses is a complex disease with three main causes being recognised:

1 Illness

Laminitis in horses can occur when an equine is critically ill due to severe infection or septic illness, such as septicaemia, colitis causing severe diarrhoea, retained afterbirth in a mare who has recently foaled, or very severe cases of colic.

Fortunately this represents a minority of laminitis cases and these horses will already be under veterinary care.

2 Overloading a limb

Overload laminitis in horses is rare and usually occurs following serious injury/fracture to the leg. The horse then overloads the good leg to avoid weight bearing on the injured leg and this excessive weight bearing triggers the onset of laminitis in the non-injured leg.

3 Hormones

The most common cause of laminitis is an underlying hormone condition. There is a complicated interplay between the following three hormonal conditions, which triggers laminitis in horses:

- Cushing’s disease (also called Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction or PPID)

- Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS)

- Insulin resistance

All three conditions increase the risk of a horse or pony developing laminitis and they can occur alone or in combination.

The actual trigger that turns them from an ‘at risk’ case into a horse or pony suffering laminitis is likely to be linked to what they eat.

The link with grass

Grass contains simple sugars and storage carbohydrates called starch and fructan. When a horse or pony eats grass, their body produces insulin and this insulin causes their cells to absorb the sugars.

However, in a horse or pony with insulin resistance, the cells do not respond normally to the insulin, so the insulin levels keep increasing and this causes laminitis. Horses and ponies with Cushing’s disease and/or EMS often have insulin resistance.

If you have a dry, hot summer, horse owners must then be vigilant in autumn if weather becomes wet and warm as there will be a rush of new grass growth.

As mentioned already, this grass is not a concern for all horses, but it is for those horses with an underlying hormonal condition that could cause the onset of laminitis.

Signs and symptoms

Subtle signs include:

- Lameness, mild to severe, affecting one, two or all four feet. Often worse when turning in circles.

- Footy or pottery when walking.

- Stiff or stilted gait, especially when going from soft to hard ground.

- Increased time spent lying down.

- Resents picking up feet.

- Reluctance to move around stable/field.

- Pain during or following farriery (a horse shouldn’t be uncomfortable after a visit from the farrier).

- Increased heat within the foot.

- Increased pulse in the digital artery.

- Divergent hoof rings (spacing between growth rings is wider at the heel than at the toe), hoof cracks, bruising or blood in the white line.

Severe signs

The following symptoms means that the horse or pony is in severe pain. This must be treated as a medical emergency and you should seek veterinary attention immediately:

- Reluctant/unable to stand.

- Groaning when moving.

- Rocking back onto the heels to take pressure off the painful laminae near the toe (see main image, top of page).

- Weight shifting from side to side.

- Increased heart and respiratory rate.

- Sweating.

- Loss of appetite.

A medical emergency

Horses and ponies with laminitis can display one or more signs, so if your horse is showing any of the early symptoms, contact your vet for advice.

Your vet is the best person to examine your horse, provide treatment and advise on the necessary management changes to assist them.

Severe laminitis is an emergency and ongoing disease can result in painful long-term consequences.

Early diagnosis and treatment as soon as the signs of laminitis are recognised will not only relieve the pain, but also reduce the risk of long-term damage.

Preventing laminitis

Speak to your vet to see if hormonal testing is advisable for your horse or pony. This could include testing for Cushing’s disease or to look for insulin resistance or equine metabolic syndrome.

Vets often see a rise in cases of laminitis during autumn, because this is the time of year when horses have a natural spike in ACTH (this is the hormone measured when testing for Cushing’s), and this spike can be related to the onset of laminitis.

Other ways to lower the risk of laminitis to your horse or pony are:

- Use strip grazing to gradually introduce horses to new grass and avoid them gorging.

- A grazing muzzle will limit the amount your horse can eat and mean they can be turned out in a larger area, but make sure you use them safely.

- Increase the amount of (and type of) exercise your horse does in order to burn more calories.

- Swap haylage for hay to lower the number of calories it provides. Soaking hay reduces calorie content even further.

- Avoid giving your horse treats, as carrots, apples and minds all contain calories. They are bad for your horse’s teeth too!

Talk About Laminitis (TAL) has been working since 2012 to raise awareness of this link between laminitis and hormonal disease, so that laminitic horses can be routinely tested for hormonal disease and therefore managed appropriately depending on their diagnosis. Find out more here.

Main image © Shutterstock. Hoof diagram © Your Horse Library/Kelsey Media