The largest and most visible organ of your horse’s body is their skin, and although horse skin conditions may be easy to spot, they can be difficult to diagnose and frustrating to treat. Skin performs a variety of important functions to support good horse health, including protection from the environment, regulation of body temperature and providing a sense of touch. Specialised areas, such as the hooves, can perform other functions too.

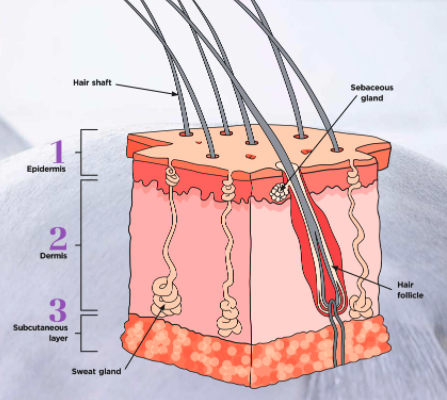

In this article, we will look at different types of horse skin conditions (including pictures) in more detail. But first, it is useful to understand more about skin, which is made up of three distinct layers, each of which acts to support the different roles of the skin:

Skin layer 1: epidermis

Diagram shows three layers of the skin

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin and it forms a thick, protective barrier made up of proteins and cells. The main protein of the epidermis is keratin — the same protein that is present in the skin, hair and fingernails of humans and other mammals. It’s also responsible for forming the hooves and horns of various species. It is keratin that gives the skin its strength and water resistance.

“Keratin is produced by special cells called keratinocytes, which are initially located at the bottom of the epidermis. As they mature, they rise through the layer until they are shed, resulting in constant renewal of the skin’s outer layer,” explains equine vet Joe Whittle MRCVS from Blackdown Equine Vets in Devon.

There are other important cell types within the epidermis too. Melanocytes produce a pigment called melanin, which gives dark skin its colour.

“Melanin helps to protect against the sun’s ultraviolet light. Invading pathogens, whether they be bacteria, funghi or parasites, all ‘look’ for breaks in the epidermis to get access to the softer, more nutritious, tissues beneath,” adds Joe.

“As a result, the majority of infectious skin conditions occur following damage to the skin’s tough outer layer. However, this initial break in the skin surface can be microscopic and difficult to see with the human eye.”

Skin layer 2: dermis

The dermis is the middle layer of the skin. It’s much thicker than the epidermis and is full of nerve endings, blood vessels, glands and hair follicles, as well as elastic proteins and immune cells. It acts to support and nourish the skin, regulate body temperature and provide sensation.

“Nerves that provide the sensation of touch, pain and temperature are located in the dermis,” says Joe. “The cells in the dermis produce the protein’s collagen and elastin, which give the skin its elastic properties and allow it to stretch to reduce the damage it suffers.”

Blood vessels in the dermis also have a role in maintaining body temperature. When it’s warm, the vessels dilate, causing heat to radiate away from the skin’s surface.

Skin layer 3: subcutis

“The subcutis is the deepest layer of the skin and consists of mostly fat and muscle tissue,” continues Joe. “The fat tissue acts as a reservoir of energy and fluids, as well as a shock absorber for the skin. The main muscle present through the subcutis is the panniculus muscle. This is the muscle that enables your horse to twitch their skin when, for example, a fly lands on them, and is an important part of a horse’s defence against irritating flies and painful fly bites.”

Hair can disguise skin conditions

Hair can disguise some skin conditions in horses, especially hairy breeds

Hair covers most of the horse’s body of course and helps to protect their skin from physical injury and damage from UV light, as well as having a minor role in temperature regulation. It can also disguise some skin conditions though and make them trickier to diagnose and treat.

Hair follicles are situated throughout the dermis, with the hair shafts protruding out through the epidermis. Horses have different types of hair, including:

- Permanent hairs that grow and do not shed, such as the mane and tail.

- Tactile hairs, such as the whiskers, which provide sensation.

- Body hairs that are constantly replaced.

“Various things affect hair growth, including genetics, nutrition, hormones, illness and the season or environment,” explains Joe. “As a result, the quality of the coat can be a useful indicator of your horse’s general health. Lots of conditions that affect your horse’s skin will also affect hair growth.

“Other glands present in the dermis secrete an oily substance called sebum. This helps to keep the skin soft and pliable, and also helps to keep the hair from drying out and becoming brittle. Excessive amounts of sebum can cause a horse’s coat to feel greasy.”

Diagnosing skin conditions in a horse

By their very nature, conditions that affect the horse’s skin are often highly visible, but affected equines can present with a wide variety of different symptoms, including:

- Dryness

- Greasiness

- Reddening

- Pruritus (itching)

- Hair loss

- Raised lumps (hives)

- Sores

- Crusts

- Oozing

- Scabs

One or more of these symptoms can either represent a primary skin condition or be secondary to another medical condition, such as liver disease or Cushing’s disease.

“If you horse develops a skin condition, it’s important to get your vet’s advice on what the likely cause might be and what treatment may be appropriate,” advises Joe. “Just because symptoms may be mild, it doesn’t mean that treatment won’t be necessary. Skin conditions can worsen quickly and it’s always easier to diagnose and treat the problem sooner rather than later.

“Getting to the bottom of a long-standing, chronic skin condition can be challenging,” adds Joe. “When your vet comes, they will ask for a full history and perform a general clinical examination, as well as a more specific examination of the affected areas of skin.”

While some skin conditions can be roughly identified from their appearance, diagnostic tests are often needed to confirm diagnosis or differentiate between possible causes. These may include:

- Hair plucks

- ‘Sellotape’ strips

- Skin scrapes

- Swabs for culture

- Skin biopsy

- Blood tests

Treatment and prognosis of skin conditions in horses will vary greatly depending on the diagnosis. Seek your vet’s opinion if you are concerned.

Horse skin conditions in pictures

Sarcoids

Sarcoids can occur at almost any site on a horse’s skin

Sarcoids are persistent and progressive skin lumps that occur mainly around the head, armpit, groin and belly. Luckily, they do not spread to other organs, but they are the most common skin tumour of horses, accounting for 40% of all equine cancers, affecting breeds of all ages and both sexes.

Unfortunately, sarcoids don’t usually self-cure and affected horses often develop multiple sarcoids at once or serially. If they sit where the tack or rugs lie, they can become irritated and ulcerated, and in the summer, flies can become a nuisance because they can bleed and weep.

Vet Sue Taylor, who runs mixed animal veterinary hospital Connaught House in Wolverhampton, says a horse’s immune system can play a big part in sarcoid formation, as can genetics.

“I find that horses with weak immune systems tend to suffer from them more,” she says. “Some horses have a genetic ability to develop an immunological resistance to them and some don’t have that ability at all. For that reason, it would be ill-advised to breed from a horse that’s covered in sarcoids, as the offspring is likely to have them too.”

Sarcoids can occur at almost any site on a horse’s skin, although there are some regions that are more liable to their development, such as the skin of the head and neck, between the front legs and in the groin area. While they can spread within the skin, they do not spread to the internal body organs. This is a huge topic about which we have a dedicated post covering more of what sarcoids look like, how they affect horses and treatment options available. Check it out here.

“The only predictable thing about sarcoids is that they are unpredictable. Some get better, some get worse, some vanish,” adds Sue Taylor.

Skin conditions: mud fever

Crusty lesions on the back of the pastern are typical of mud fever

More correctly called pastern dermatitis, mud fever is commonplace. It’s the name given to a specific set of symtoms that cover a wide range of possible causative agents. It’s often caused by the bacterium Dermatophilus congolensis, which thrives in damp conditions.

If your horse is affected by mud fever, you will be able to spot crusty lesions on the back of their pastern and down to the heel. These can be very sore, even leading to lameness in severe cases. Mud fever is often the result of horses spending too long standing in wet conditions, with the wet (rather than mud) damaging the skins natural protective barrier. It’s a pain to tackle once it’s set in and so prevention is always better than cure. Find out how to do that here.

Mud fever can be a real pain — for the horse physically and for you figuratively as their owner trying to manage it. I’ve known horses suffer with a touch of mud fever just from going hacking and not having their legs cleaned and dried thoroughly afterwards. My favourite way to manage legs that are very wet and muddy is dry/rub the worst of the mud off with straw, and then brush the rest off as soon as the mud is dry, ensuring the horse has a lovely deep bedding to stand in in the meantime.

I used to hose muddy legs off, but I’ve found that the constant wetting and rewetting of legs doesn’t work well for my horses, who are mostly sensitive Thoroughbreds.

3 Rain scald

A flaky coat with ‘paint brush’ clumps of matted hair is seen with rain scald

Dermatophilus congolensis, one of the bacteria that can cause mud fever (see above), also causes the sores on the body, head and neck of the horse that are commonly known as rain scald. This condition is characterised by ‘paint brush’ clumps of matted hair, with oozing, crusty lesions underneath.

Despite the name, it isn’t caused by exposure to the elements, according to Ben Curnow, a lecturer at Liverpool University’s equine vet school Leahurst who has a special interest in equine dermatology, but most commonly by the warm, sweaty conditions under a rug.

“The main cause is when a wet rug stays on the horse from wet to dry,” says Ben. “The damp conditions allow the bacteria to take hold. I most commonly see rain scald in horses who haven’t had their rugs removed for a couple of days. With good husbandry there is much less risk of this happening.”

This skin condition generally clears up within 14-21 days if the horse is kept indoors and unrugged. Essential oils may also be helpful for recovery. In 2019, researchers from Virginia, USA, found that a spray made of 1% tea tree oil in baby oil sped up the healing of lesions caused by rain scald. Learn more about rain scald here.

Skin conditions: lice

Lice can be seen at the base of hair or on the horse’s skin

Lice can trigger skin conditions in horses, with two types of lice likely to cause an infestation:

- Bovicola equi, a biting louse that attaches to the host’s body hair and eats skin debris and secretions.

- Haematopinus asini, a blood-sucking louse that likes the coarser hair of the mane, tail and feathers and uses its mouthparts to pierce the skin and drink blood.

“Lice generally affects old and young horses — youngsters who, as yet, have no immunity, as well as older horses, especially those with the woolly coat caused by Cushing’s disease,” explains Ben. “You’ll see patchy hair loss on the back and belly of such horses and it will be really itchy.”

Horse lice are 2-5mm in size and so can be seen with the naked eye and are usually found around the base of the hairs or on the skin. They often come to the surface when the horse sweats.

Lice like the thick coats of cobs and native breeds and they are most common in winter or early spring. They love the sweaty atmosphere under a rug and so one way to deter them is to not over-rug. Ben suggests that owners should treat lice with a spray or a powder containing an insecticide like cypermethrin.

He says: “Use a licensed product like Deosect once and then again two weeks later. The product doesn’t kill eggs and so you need the second treatment to catch any that hatch. Clipping the horse will make them much easier to treat and also less attractive to mites.”

Why isolation is so important

Horses with skin conditions like lice need to be isolated as the insects pass easily from horse to horse, while all rugs and other equipment that has come into contact with that particular horse should be washed and disinfected.

Researchers at Bristol University found that essential oils can be helpful to deal with lice infestations in horses in a 2023 study. They treated a group of donkeys infested with Bovicola equi with either a 5% solution of lavender or tea tree oil, or an inert control substance, and after two treatments they found that the lice infestation had dropped by 78% on the animals treated with essential oils. The infestation either stayed the same or increased on the donkeys treated with the control substance.

Suzanne Harris, who runs natural animal health consultancy Tara, has experience of treating lice with tea tree oil.

“I took on a donkey from the Donkey Sanctuary who was already riddled with lice when he came to them and they had been treating it with a solution of tea tree oil. I kept up the applications and it worked really well,” she says.

Skin conditions: chorioptic mange

This horse with chorioptic mange has injured themselves trying to stop the itching

Chorioptic mange, also known as feather mites, is a particularly distressing and itchy skin condition in a horse. The first signs of this skin condition that an owner will see are the horse stamping their feet and rubbing or chewing their legs.

These microscopic biting insects (Chorioptes equi) are difficult to see with the naked eye — they measure just 0.3mm — but sometimes the crusts that form move, and therefore look rather like ‘walking dandruff’. Horses with mange can become so distressed that they inflict injuries upon themselves trying to reduce the itching.

Treating mange can be complex, as the insects often spread into the horse’s environment — where they can live, off the horse, for around 70 days — and other horses on the yard may be harbouring mites, but not yet showing symptoms. If caught early enough, it may be possible to avoid having to remove the horse’s feathers, but once severe, clipping the legs is necessary.

“It’s important to involve your vet in treatment for feather mites,” advises Ben. “They can prescribe Dectomax or ivermectin injections, which when used two weeks apart are effective. There are also topical insecticide drugs that are popular with people whose horses have chronic progressive lymphedema (CPL) and are prone to mites.

“A good preventative is to wash your horse’s legs with Head & Shoulders clinical strength, which you can buy online. It contains seleniumsulfide. Leave it on the legs for 15 to 20 minutes before washing it off. It gets rid of scurfy skin and keeps mites at bay.”

Re-occurrence of mange is frustratingly common, adds Ben, and regular treatments are necessary for many horses.

Skin conditions: ringworm

Ringworm is easily spread between horses, people, tack and other animals

Ringworm is is the most common fungal infection of horses in the UK and, contrary to its name, it’s not caused by a worm and does not always present as a ring. This itchy horse skin condition can occur at any time of the year, but is spread by sharing rugs and other equipment and is most prevalent in the winter and spring. It is typically caught by young horses who haven’t encountered it before and occurs in older horses after a stressful incident when their immunity is low.

Ringworm is caused by a number of different fungi and is easily spread to other animals, including humans, so owners should ensure that they wash their hands carefully if ringworm is suspected.

“Ringworm can be a distressing episode for a horse, but it can be treated very effectively. It is generally introduced by a new horse, or one who has come into contact with an infected horse,” says Ben Curnow.

Mildly affected horses with ringworm will usually be well in themselves, though some may attempt to rub the ringworm patches and the condition can make them feel sore and itchy. Left untreated, ringworm can start to damage the coat and can take up to several months to ‘self-cure’, occasionally developing into a serious health problem. Therefore, treatment is usually the best course of action. More on that here.

Allergic skin disease

A well-rubbed tail, typical in sweet itch sufferers

Allergic skin disease can be extremely difficult to manage in horses. Patients generally present with pruritus (itching) — which may be widespread or localised — and there may also be hair loss, hives and sores due to the horse rubbing against things in an attempt to relieve the itching.

“The allergy can either be the primary cause of the problem, or an important underlying cause for other skin conditions,” says Joe Whittle. “Horses can be affected by a wide variety of possible allergens, but insect bite hypersensitivity, more commonly known as sweet itch, is by far the most common.

“When diagnosing allergic skin disease, it is important to rule out other causes for the itching as such bacterial, fungal or parasitic infection. It’s then a matter of identifying the allergens responsible.”

A blood test is available although intra-dermal skin testing provides more accurate results. The best treatment for allergies is to avoid the causative allergen as much as possible. If this isn’t practical, or doesn’t completely alleviate the problem, then medication to reduce the itching, primarily corticosteroids, can be used.

“Allergen Specific Immunotherapy (ASIT) is used to desensitise the horse to the allergen and is a useful tool in getting allergies under control,” adds Joe.

Allergic reactions

Hives (swellings) on this horse’s neck are the result of an allergic reaction

Allergic reactions in horses can be caused by a wide range of things such as food, pollen, dust, insect bites, moulds, grass, trees, injections and grooming products, such as shampoos. Response to allergen exposure can vary massively from a localised skin swelling to hives. In more severe cases, exposure can lead to anaphylactic reactions and death. Learn more here.

I have experienced a horse having an allergic reaction to a wormer. He was the first of three horses to be wormed on a large yard, and after finishing the third horse my sister and I noticed that Mr Buckle wasn’t looking over his stable door. Thinking it odd, as he was a very sociable ex-racehorse, we walked to his door to find him lying flat out, thumping the side of his head on the floor.

When he saw us he got to his feet, and on examining him we noticed that the left side of his mouth — this was the side where I inserted the wormer — was swollen. Top and bottom of his mouth on that side were affected: it looked like he was hiding a balloon in there. While my sister went to call the vet, I washed Mr Buckle’s mouth by holding a running hose (flowing lightly) against his mouth. Then I walked him around to keep his mind off it. Seeming no worse for wear, the vet’s advice was to monitor him and call back if anything changed. As it happened, within the hour the swelling had subsided.

We avoided using that wormer again for Mr Buckle and he never had any more problems. He lived with us until he died, and his swollen mouth was one of the strangest days during those 15 years!

Skin conditions: melanomas

Melanomas are a common sight on grey horses

Melanomas are a form of skin cancer that occur mostly in grey, white and cremello horses of any breed and gender. There are three main types of melanoma, and the size and colour of your horse’s lump, or lumps, will vary depending on which type of tumours they are.

“Sadly, there’s no way to prevent your horse from developing a melanoma, and if they’re grey or light coloured, the chances are they’ll be affected at some point in their life by one or more lumps,” says equine vet Paul Smith, director at North West Equine Vets.

“If your horse is lucky, this may simply be a one-off, slow-growing, benign melanoma that doesn’t cause any problems, or they may be unlucky enough to suffer a cluster of fast-growing, aggressive lumps. Unfortunately, there’s no way to tell, and nothing you can do to stop them developing in the first place.”

Paul talks about melanomas in more detail here.

Images by Shutterstock, Your Horse Library & XLEquine Vets. Illustration by Your Horse Library/Geoff Johnson